My father died 20 years ago today. His death fucked me up pretty good. Actually, his illness didn’t do a bad job of fucking me up either. Watching him deteriorate from a strong and vital man into a shell of a human being, someone I barely recognised, sent me plummeting into the deepest and darkest depression I’ve ever experienced. The ten months of his illness were agonising, and the months afterwards were very much worse.

Until my father died, work was a source of great comfort for me. A place I could escape the gnawing torment of his decline. A place of relief from the anguish. I was working as a junior air traffic controller at Moorabbin, which is a busy airport full of training aircraft. It’s chaos. Delving into work, my focus was laser sharp and blinkered, all the better to not allow any thoughts of my father to seep into my consciousness. I was depressed, yes, but I was functional. In stark contrast, after Dad died, I became catatonic. I couldn’t eat, I couldn’t sleep, I couldn’t do anything. And I certainly couldn’t work.

I was off work for three months, and spent all that time at our family home with my Mum and sisters. I slept in the living room on a foam mattress which I made up every night, and packed away every morning. Sleep was elusive; my head filled with swirling memories and jagged thoughts that were so painful I would just sob into my pillow for hours. I was eventually prescribed sweet, merciful Temazepam to help with the debilitating insomnia, which was a life buoy thrown to me when I was drowning in a tempestuous sea of grief. My waking hours were spent staring into space. Aimlessly shuffling from room to room. I was completely numb and I don’t remember much from that time. I lost a lot of weight. I rarely left the house. I cut myself off from all my friends. My father’s death knocked me out. It was a king-hit that took me more than 18 months to emerge from.

My mother never resurfaced from her loss. When Dad died, a very large part of her did as well. She never stopped loving him with all her heart, and she stubbornly refused to live a full life without him. To my Mum, Kon’s ashes embodied his soul, and until the day she died she kept a lit candle beside his urn on the mantelpiece in the living room. She said goodbye to him when she left the house, and hello when she returned. Goodnight when she went to bed, and good morning when she woke up. It was her way of staying connected to him, even though he was gone. It was her way of keeping him alive, and that gave her comfort.

My mother’s death hit me very differently. Firstly, even though I knew she was sick, I didn’t know that she was at death’s door, so I was totally unprepared. Secondly, she was my mother, not my father. And thirdly, after Dad died, I still had my Mum around for another 15 years. But when she died too, suddenly they were both gone and I experienced not just the loss of a very important person in my life, but the loss of my roots, my anchor, my family unit, and my very foundation. And the loss was profound. I didn’t get depressed, like when Dad died. Instead I succumbed to an extreme and overpowering sadness, the depth of which I could never have imagined possible. The sadness that I felt was not normal. My whole life leading up to this event, sadness was a room on the ground floor. Maybe when things got really bad, it went down to the basement. But suddenly, when my Mum died, I realised that it was not the lowest, or the worst, that I could feel. I learned that there were twenty cavernous levels below the earth that could fill up and overflow with my sadness. It’s like when people say you don’t know how much love you can truly feel until you have a baby. Well, maybe you don’t know how much sadness you can feel until you lose your mother.

I’ve spent the last four and a half years since my mother’s death fiercely grieving her. I miss her deeply and still sometimes cry myself to sleep when it just hits me in the chest that she’s gone and that she’s never coming back. I think of her every single day. I see her picture on my bedroom wall every single day. And every single day something reminds me of her, and I’ll say emphatically, “I love my Mum”. Because I really fucking do.

Conversely, in the last four and a half years, I have hardly thought about my Dad at all. Deplorably, I haven’t had any room in my heart for him. And I feel so incredibly guilty that the all-consuming grief I feel for Mum has completely supplanted the grief that I was holding for my Dad. And of course, intellectually and emotionally, I know (I know!) that I still love my father and I know that I miss him and I know that I grieve for him. And of course it’s not a competition about who I love or miss the most. But I am grateful that this, twentieth anniversary of his passing, is an opportunity for me to once again focus on my Dad, and to once again make some room for him in my heart where he belongs.

My parents were very different people, and had very different parenting styles. My Mum was all heart, loving, open and warm. My Dad was more outgoing and filled the room with his personality… which could sometimes be a lot. He had been raised in a household where the man was in charge, the man was the be-all and end-all, the man wore the pants and the man had the last word. My Dad’s gentle nature prevented him from becoming the kind of authoritarian parent that his own father was, but still he could be pretty strict and uncompromising, especially when my sisters and I were teens. I think that when his three daughters started growing up, it triggered an internal clash between his easy-going personality and the stern parental conditioning he’d grown up with. And this started causing a rift in our family. Being the first born child, being the one for whom rebellion simply wasn’t an option, I accepted all the rules. I was the good girl. And I’m grateful to both of my sisters, for being significantly more ballsy than I was and smashing down the barriers that had been put around us. I’m grateful because, even though it caused a great deal of heartbreak and strife and tension in the house at the time, it was the catalyst for our father to change. As a parent, and as a man.

I have to give my Dad props for being able to shed generations of toxic masculinity, and to look inwards and realise that he no longer had to be so overprotective and controlling of his daughters. He understood that if he didn’t make changes within himself, he was at risk of pushing us away, or even losing us completely. And he changed. He just did it. He softened, he became more accepting, and he became more affectionate and open and loving. He became more himself. It was a truly remarkable transformation. Over the years, my relationship to my Dad evolved from worship, to reverence, to fear, to shame, to disrespect, to ambivalence. And then I went back, and I got to know him as a person, as a human being. And I started loving him again. And finally, at the end, after all that, we were friends. I’m so grateful that we had the opportunity to complete that circle while he was still alive.

I have so many beautiful memories of my extravagant and irrepressible father, whose extraordinary zest for life left an impression on everyone who knew him. Even though it may seem trivial, a memory that I hold very dearly is of how gentle my Dad was when he put my hair up in a ponytail when I was a kid. As opposed to my Mum’s confident and efficient method of whisking my hair up and quickly twisting the hair-tie around the ponytail, my entire head fit into my Dad’s enormous hands as he tenderly stroked my hair, trying so hard to not pull even a single one as he lovingly gathered it up on top of my head. And I knew, I just knew, even then, as a five, or six, or seven year old, that it was a special moment between us. I cherished that moment when I was a kid. And I cherish it now.

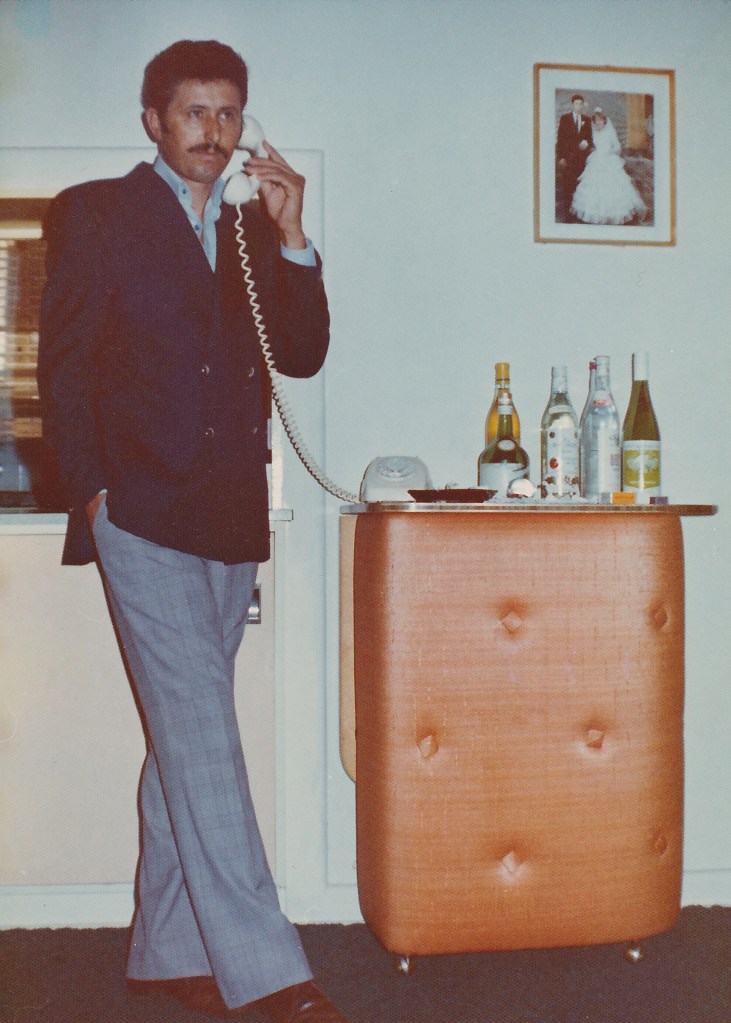

One family story that became legend over the years demonstrates how meticulous and fastidious Dad was about certain things. He always took such great pride in the way that he looked, and in particular the clothes that he wore. His sisters, Dimitra and Sophia, recently recalled the story for me, setting the scene at a large family dinner. Dad, Mum, aunts and uncles and friends of the family were all there, gathered around the table. Someone was carving and serving a large roast chicken, and a few droplets of gravy splashed onto my Dad’s shirt. As was his wont, he became very upset. Everyone there was accustomed to witnessing Dad’s over-the-top reactions whenever he got even a minor stain on his clothes. But this time, apparently, he became so melodramatic about it that my Aunt Sophia (who was up to here with Dad’s histrionics) lost her patience, and lost the plot. Wild-eyed, she pushed her chair back, walked around the table to where my Dad was sitting, grabbed the chicken drumstick off his plate and furiously started rubbing it all over his shirt, yelling, “It’s just a fucking stain, Kon!!!” As you can imagine, everyone was so shocked at the unexpected insanity of the moment, they all burst into laughter. Everyone, that is, except my Dad, who sat frozen like a statue, staring straight ahead with a stony look on his face.

Thinking back, I remember lots of stories from my Dad’s youth. Like the time a tree he was standing right next to was struck by lightning. Knocked out by the impact, my father lost his sight and couldn’t see for hours afterwards. When his eyesight returned, he went back to the tree, which had been cleaved in two, and found a stunning gemstone in the cradle of the split trunk. The stone was a brilliant azure blue, and I remember seeing it and holding it and being in awe of it when I was a kid. My Dad treasured that gemstone, and I wish with all my heart that I knew where it was.

My father’s family were so poor that his parents couldn’t afford to feed all six of their children, so when my Dad was 17 years old, a deal was struck to foster him out to some neighbours, a rich family that lived just down the road. Until then, my father had never even worn a pair of shoes. So the pride that he took in his clothes later on in life makes total sense to me. The couple that “adopted” my Dad were in their sixties and didn’t have any children, but they promised to secure him financially and to love him like their own. The first few months went smoothly, and Dad helped them on their farm and generally did whatever was needed around the house. He even used to drive the couple to church every week. In a village where most families couldn’t even afford a bicycle, this was a big deal.

After a while though, the couple started talking about weddings, suggesting that Kon marry their niece, but he wasn’t interested. So the old guy started imposing a curfew, saying that my Dad (who was 19 years old by that time) had to be home by 10pm on Saturdays. Obviously this was total bullshit and Kon justifiably stayed out until the wee hours of the morning that first weekend. He did the same the weekend after. And on the third weekend in a row that he came home late, he found the door to the house locked. And that was it, that was the end of the deal. That Sunday morning, his younger brothers and sisters woke up to find Kon sleeping on the floor next to their beds, and the whole family rejoiced that he was finally back where he belonged.

Kon Stathopoulos was a singularly brilliant man. He pulled himself out of abject poverty in Greece, and created a whole new life for himself in Australia. He completely rewrote his destiny. My Dad was a dreamer and a big thinker! Sure, he drove trucks, and then later taxis, but my Dad was too big to be a taxi driver forever. He worked some shitty jobs to make ends meet, but in his spare time he was an enthusiastic entrepreneur. Bow ties, light up yo-yos, silver screens for cars, decorative ceramic tiles. He tried a whole bunch of innovative business ideas before finally starting his own company, Plastercraft Contractors.

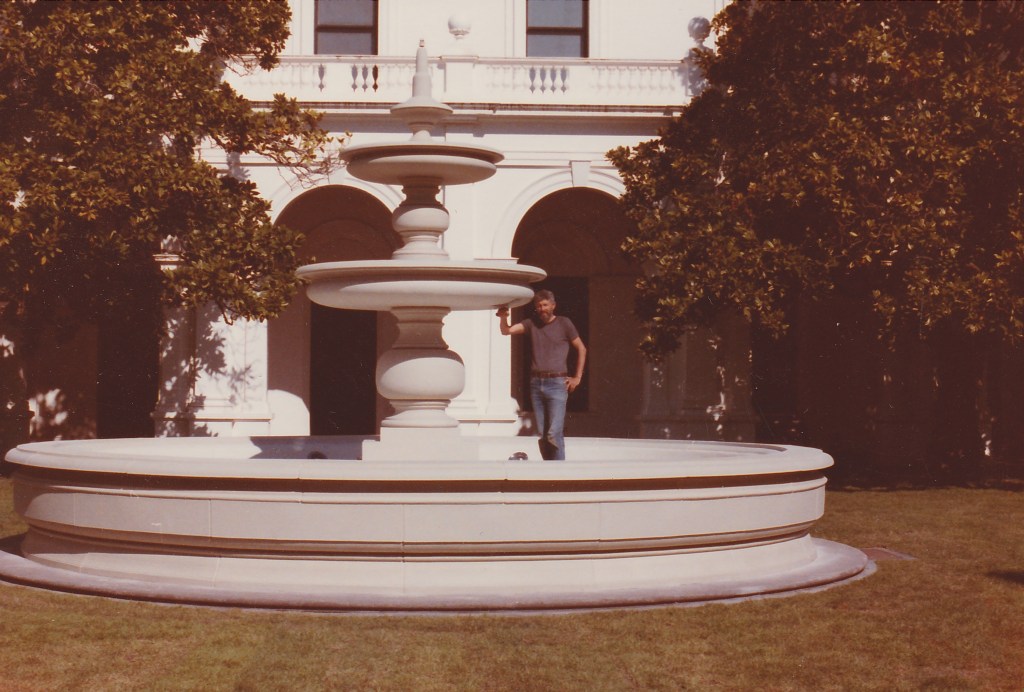

A one-man show, my Dad took solid plastering to the next level, turning it into an artform. Within just a couple of years he had built such a great reputation in the industry that he was asked to singlehandedly restore the exterior of a large church in Ballarat. He was also commissioned to create a new plaster cast emblem for the Red Eagle Hotel, in Albert Park, the very same bar where Kylie Minogue had her 21st birthday party!!! He then landed the extremely exclusive job of re-designing and building the beautiful and iconic fountain at Government House in Victoria. Every year on 26th January, Government House opens its doors to the public, and thousands of people get a chance to peek inside the stately home and to roam through the gardens. There are also monthly tours of the 11 hectare garden which anyone can book, so why not go along on one of these tours and see for yourselves the amazing sculptural achievement created by my very own father.

.

.

Later on, due to the success of his business Dad expanded into larger scale projects like apartment building construction sites. He often invited me to join him and earn a little bit of extra cash, and I once hit the jackpot, making $400 in one week being an elevator girl, asking big burly construction workers wearing hardhats, “Which floor?” for eight hours a day. It was here that I first saw the man that my father had to be when he wasn’t with his family. For the first time, I heard him casually throwing around words like, “fair dinkum”, “bloke”, “smoko”, and I even heard him say “fuck” a few times. My brain exploded. As a 21 year old I’d never heard my Dad swear at home, yet here he was cursing with such ease and regularity. It was surprising, but also kind of nice, to discover this other side of Dad that I’d never seen before. It added yet another dimension to him.

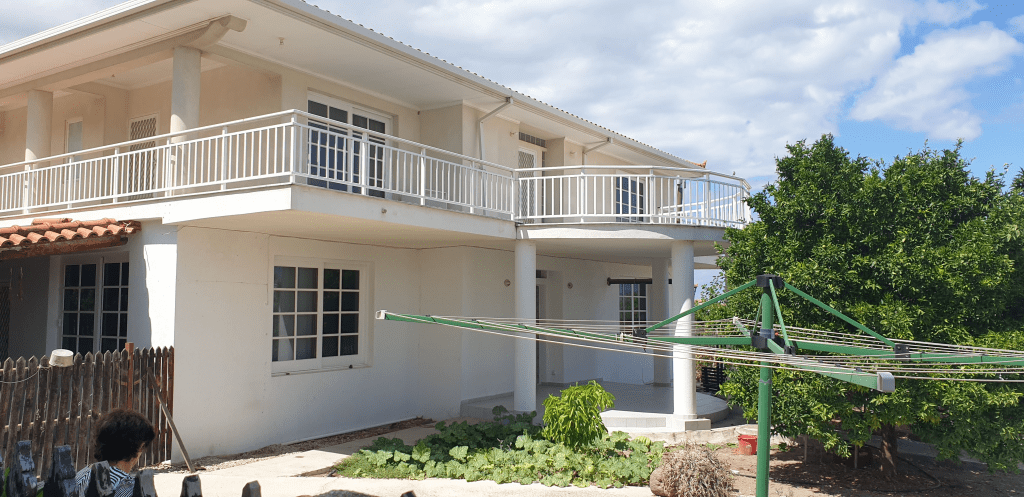

My Dad left his mark on some pretty important buildings, but his passion project was building a holiday home for our family in Ancient Korinthos, in Greece. The construction took him several years, and was (mostly) finished just before he was diagnosed with lung cancer in 2002. His dream was for the five of us to holiday there, as a family. But tragically, he never lived to see that happen. The house is still there, an empty monument to one man’s vision.

.

I have a cute little blue urn on my bedside table, which holds a little bit of my Mum’s ashes and a little bit of my Dad’s ashes all mixed together. I thought that having my parents close to me when I sleep would provide me with some sense of closeness to them, like my Mum used to get from having Dad’s ashes near to her. But I was wrong. I get nothing from it, except an academic understanding that my Mum and Dad’s cremated remains are next to me when I’m in bed. I have no response to it at all, emotionally. Sometimes I’ll shake the urn, and listen to their bone fragments rattling inside. I know what’s in there, I know that it’s them, but even so, there’s no connection to who they were when they were alive. I wish there was.

My Dad really shaped the first 32 years of my life. His first job in Melbourne was in the inner-city suburb of Carlton. So naturally my father was a Bluebagger. Therefore I am a Bluebagger. Dad inspired my love of tennis, and I played competitively for years, even aspiring to turn professional when I was sixteen. He taught me all the tricks of how to play a solid game of backgammon. When I was 15, he taught me how to drive a manual in a rusty old Land Rover on a hilly farm with no roads. And once I’d mastered that, he took me to an abandoned industrial estate in Springvale to learn how to drive his crappy work van. The one with the dodgy clutch and the sticky column shift. And once I could drive that, I could drive anything. I’m pretty sure that the reason I love to throw epic parties (and I really do love to throw epic parties) is because I inherited my Dad’s passion for entertaining, and showing people a good time, and living large. It’s funny, what gets passed down from father to child. Being a sports fan can be one of those things. Wanting things to be just right, might be another. A house in Greece, another still. But maybe a zest for life and knowing how to dream big are the most important things a man can pass on to his daughter. Thanks Dad.