My husband, David, has been an air traffic controller for over 35 years, and you can bet he’s got some juicy aviation tales to tell. One of my favourite anecdotes is an oldie but a goodie from when he was doing ground control at Dubai International during a crazy busy shift. Every pilot wanted a piece of him and he was trying to prioritise and get to everybody in turn, but one pilot in particular kept interrupting him to ask about his position in the queue. David told the guy to standby a couple of times, but the pilot obviously didn’t care about the chaos on frequency because he just kept nagging and nagging (which, by the way, is incredibly poor airmanship). Eventually David just had enough and snapped at the pilot, “Mate, I’ve got 75 things to do, and you just became number 76! STANDBY!” This comment has, justifiably, become legend over the years.

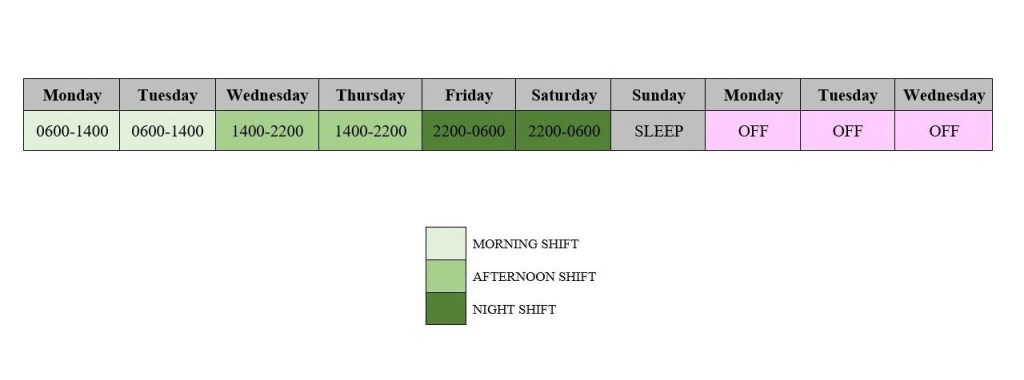

One of the joys of being married to another air traffic controller is the after-work debrief. While David and I actually work at different airports in Dubai, we do work the same shift pattern, so we arrive home from work at around the same time. After several years of marriage we’ve settled on the ritual of greeting each other with a kiss, putting away our work stuff, getting changed into comfy clothes and then decompressing. Thirty minutes maximum. And in case you were wondering, yes, there is always (always) something to decompress about. Being able to vent to somebody who understands ATC is a game-changer, because they get what you’re talking about in a way that a normie simply could not, no matter how much they tried.

So what do we whinge about? Well, some of the time it’s about management, but mostly it’s just about the bloody pilots. The men and women we talk to all day, moving them around like pieces in a 3D chess game. It often feels like pilots think they’re the only aeroplane on our board (as demonstrated by #76 in David’s example above). But we are the ones that have the big picture. Only we know where everything fits, and that is why pilots must do our bidding. To ensure that everything flows safely, expeditiously and in an orderly fashion.

When I walk home through the arrivals terminal at the end of a shift, I often intermingle with the passengers that have just disembarked from an aircraft. And just like the Red Sea, the crowds always seem to part for the pilots, confidently strutting through the terminal in their crisp, smart uniforms. Sure, they might get all the adulation, and even I begrudgingly have the utmost respect for airline pilots. But at the end of the day it’s the anonymous woman camouflaged in her civvies walking amongst the masses that the pilots have to answer to. In my tower, when I give an instruction to a pilot I expect them to comply. In fact, if they don’t comply, I’m obliged to report them to the regulator. That’s how much sway air traffic controllers have over pilots (we are what it says on the tin). But we don’t issue instructions willy nilly. There are rules, and we have to be able to justify every single instruction that we give (in the subsequent court of inquiry, as we like to say in the biz). Everything we do is recorded and everything we say is recorded. Every mouse click, every finger on a touch screen, every glance through the binoculars. Even my carefree dancing in the tower at 2am on a quiet Friday night, is recorded on CCTV.

Unfortunately, “failure to comply with ATC instruction” is common and routine. It happens every single day, though it doesn’t always result in a big drama. If I tell a pilot to turn left on a taxiway, and they turn right, it’s not the end of the world. No-one’s going to die. But it’s still a failure to comply, and a report needs to be submitted. Also, it’s a fucking pain in my ass because I’m the one that has to fix it. Most of the grievances that David and I share at the end of the workday stem from things like this. Pilots that just don’t do what they’re told. Pilots that just don’t listen. Even the simplest instruction of, “Turn left on zulu, right whiskey 8, hold whiskey 8 bravo” will sometimes be read back as, “Right on, um zulu, right victor, hold… um”. To which I will gently respond by saying, “Negative” and then patiently repeating the instruction. When they get it wrong again is when I change my tone. I do not raise my voice, but it is quite clear from my tone that I am not impressed with the pilot, and that they are wasting my time. I repeat the instruction once more, this time imbued with that tone, and if they get it wrong again (which trust me, they do) I issue a stern “hold position” instruction, and carry on with the other aircraft under my jurisdiction. I do not do this to be punitive. I do it because this pilot obviously needs special attention and I do not have special attention to spare at that particular moment. Usually, by the time I get back to them, they’ll have sorted it out and we can all get on with our day. I don’t think it’s rude to say that it’s the business jet pilots that give me the most trouble. In comparison, commercial airline pilots are the epitome of professionalism. And (quite rudely) I will leave those two facts there for you to make the connection.

As I said, I don’t punish pilots for fucking up. We’re all human, and we all make mistakes. But some air traffic controllers do, which I think is unbecoming and unprofessional. A young colleague recently boasted to me of how he humiliated a pilot that had made an error after landing, berating him all the way to the parking stand. I was not impressed with this show of immaturity. When David told #76 that he’d been relegated to the end of the queue, he didn’t mean it. The aircraft held its place in line, but I guess the pilot didn’t realise that, and ended up complaining (which is how the story became lore).

Aviation is a system that utilises redundancies to compensate for all the messy humanness of the people that use it. We all have to remember that there is a human being on one end of the radio, and a human being on the other end; and when a pilot makes that first call to you, a human connection is created. They are not aeroplanes and they are not call signs. They are human beings. With all their quirks and weirdnesses and stupid dad jokes. When I first started out in Melbourne airport, a Russian IL76 had made a stopover and was parked on one of the outer taxiways. Most of us had never seen one before, and one night a Qantas pilot taxiing past asked me, “What type of aircraft is that?” I naively responded, “Apparently, it’s an Ilyushin,” to which he wisecracked, “No, no, it’s definitely there, I can see it with my own eyes”. Groan! I guess I walked right into that one.

About 12 years ago a Russian cargo plane was in a hurry to depart Al Maktoum so that he could make his strict arrival slot time in Kabul. As he was taxiing to the runway, a colleague of mine spotted smoke coming out of the engines and as I turned to look, even greater plumes of white smoke started pouring out. As is standard procedure, we pressed the crash alarm button to alert the Airport Fire Service of an aircraft ground incident, and I instructed the pilot to hold position. He objected and kept taxiing, saying that he had to make his departure slot time. I heard the commercial pressure that he was under, and the stress, in his voice, but I insisted that he hold position and told him that the fire trucks were on their way to inspect the aircraft due to smoke. He ground to a screeching halt and started yelling at me that it was completely normal to have smoke coming out of the engines of this type of aircraft. But I didn’t know if that was true. It might have been, but still, I wasn’t comfortable letting him depart. Imagine if I’d let him go, and he crashed shortly after departure (don’t forget that court of enquiry I was talking about earlier, I never do). I allowed the pilot to rant and rave, as he was the only aircraft on my frequency at the time, and after he’d exhausted himself and come to the realisation that he wasn’t going anywhere, I invited him up to the tower to have a chat about it. He stomped up the stairs in his khaki jumpsuit, smoke coming out of his ears, angry and ready to fight. But I greeted him politely, offered him a cup of coffee, and showed him exactly where it was printed in my instruction manual that I had no choice but to call the fire service in a situation like that. Fifteen minutes later, he left, all sweetness and light. We smiled and shook hands before he walked down the stairs and out of my life forever. I like to think that he didn’t get into trouble over the incident, or lose his job because he missed his slot, but I really can’t be sure.

So we develop relationships with pilots, even if it’s just for the few minutes that they are on our frequency. (One colleague from Melbourne tower took this to the next level and actually married one!) We crack jokes. We get shitty with each other. We all say happy new year when the clock strikes twelve. We all shared an eerie feeling of shock, support and camaraderie on 12th September 2001. Sometimes we misunderstand each other or we make a mistake, and when that happens the other one will either laugh it off or they’ll rub it in and say I told you so. I was taught the old-school way of never apologising to a pilot, even when I’m wrong. But that’s not my stripe. I have a little replay button on my comms screen that I can use to go back and check what was said, and if I’m the one that made the error, I’m more than happy to admit it to the pilot and to say I’m sorry. The response is always respectful gratitude, which is its own reward.

More recently at Maktoum airport I was working the doggo, which is when I turn on my night shift voice (you know – smooth, dulcet, graveyard-shift, radio DJ vibes). I had a couple of planes on the go and as one of them taxied to his stand, he said, “You know, you have a very lovely voice”. The other pilot piped up and added, “I was just thinking the same thing, it’s so reassuring!” This totally made my night, and I spent the next 30 minutes blushing to myself in the tower.

As I said earlier, we don’t have any passenger airlines based at my airport, but we do have a couple of helicopter operators, one of which is the Dubai Police Airwing and the other, a commercial helicopter operator called AeroGulf. Flying for almost 50 years, their bread and butter is offshore flights ferrying Dubai Petroleum staff to and from oil rigs, which they do out of Al Maktoum several times a day. Recently, the UAE’s General Civil Aviation Authority’s preliminary report of the helicopter accident that occurred offshore on 7th September 2023 stated the following:

An AeroGulf Bell B212 Helicopter, registration marks A6-ALD, was scheduled for a non-revenue training flight for night operations to an offshore helideck under call sign Alpha Lima Delta (ALD). The Helicopter took off at 1518 (UTC) from runway 30 of Al Maktoum International Airport (OMDW) for the offshore ARAS driller rig located in Umm Al Quwain. There were two flight crewmembers onboard.

Later in the report:

At 1605, the Helicopter took off from the rig and changed direction heading northwest and continued the flight. One minute later, at 1606, the Helideck Landing Officer (HLO) reported that the Helicopter had crashed approximately 600m away from the rig in the northwest direction. At 1608, a distress call for search and rescue was initiated.

What the report fails to mention is that at 1730 GMT, I walked up the stairs into the air traffic control tower at Al Maktoum airport to commence my night shift. As soon as I got there, I knew something was wrong. I asked what was going on and was told that A6-ALD had crashed into the sea. My breath caught in my lungs, and I felt like I’d been kicked in the chest. Oh my god. I was asked if I was OK to work the shift, and I said yes. Of course. I was OK, but still devastated and fearful for the safety of the two pilots on board. I talk to these guys every single day. I’ve never met any of the AeroGulf pilots, but they’re my guys. When I am on shift, I am responsible for them. And two of them were now missing and presumed dead. And I didn’t know which ones. During my shift the police helicopter operated under the Rescue callsign, searching for the pilots and the wreckage in the inky darkness of night, returning to refuel and then take off again to continue the search. I could hear the exhaustion and the hopelessness in the police helicopter pilot’s voice. I hoped that he could hear the compassion and hope in mine. In the early hours of the morning the police helicopter landed one more time and taxied back to their hangar for the night. The search would resume in the morning.

The body of one pilot was found the next day, and the second pilot’s body was found two days later. Even though I had known that the impact of a helicopter crashing into the sea would be fatal, I (and I’m sure many other people) had held out hope that the pilots would somehow survive. That maybe they’d been picked up by some fishing boat. But sadly, that wasn’t the case. All that remains now is for the full investigation to reveal what happened on that fateful night.

About a month after the crash, my curiosity got the better of me and I asked a colleague if she knew which of the AeroGulf pilots had died. She tried to describe the voice of one of them, and my heart just broke. She was describing my favourite guy. Super friendly, very good at his job, someone I could always rely on. Even though I’d never met him, and even though I didn’t know his name, we had a relationship. I felt like we could trust each other, and that we had each other’s backs. I would issue him clearances that I would never give to other helicopter pilots, simply because I knew that he understood my instructions perfectly. He was switched on and reliable, and not all pilots are. Of course it didn’t make a difference that he was my favourite, the fact was that two men had died and I was really sad about that. But knowing that I would never hear his lovely, cheerful voice again was heartbreaking.

The very next day, when I arrived at work I saw a flight plan for an AeroGulf helicopter, so I wasn’t surprised when a pilot called me for an airways clearance. But I was shocked that the pilot who called me was my guy!!!!! He was alive. He’s alive!!! I can’t tell you how happy and relieved I was to hear his beautiful voice. But I felt conflicted, knowing that my joy was a slap to the faces of the two pilots who did die. I felt disgusting, but still revelled in the relief of knowing that my favourite pilot was alive and well. It took every ounce of professionalism for me not to tell him that over the radio.

And now whenever I talk to my AeroGulf pilot, I like to think that I’m conveying in my voice how deeply happy I am to hear his. How happy I am that he’s alive. In my tone, I also try to convey my deepest condolences for the loss of his colleagues. I often think about how he might be scared to be flying around without yet knowing what happened to them. And I often think about how sad he must be. I wish to convey in my voice all of these things when I issue standard instructions like, “Take off your discretion”, “Join right downwind runway 30”, “Taxi via zulu, victor seven, back to AeroGulf”. And with every single instruction that I give him, every single thing that I say to him, my voice is heavy and thick with meaning.

And when he departs my control zone on his way out to some oil rig and I instruct him to “Broadcast MBZ 134.65”, I hope that he can hear in my voice how much I love him and how much I hope that he comes back. How much in my heart I’m saying, please, please, please, please, please, please come back. Please be safe. Safe travels. I’ll wait for your return. I’ll be here. I’ll be waiting. Because two of his colleagues never came back. They left Al Maktoum airport and they just never came back. And I can’t imagine how that must feel. So I just hope that he can sense how much I care for him, as I care for all the pilots under my control. I’m looking out for each and every one them. It’s my job to keep them safe. It’s my job to send them all out into the world, and to bring them all back home again, safe and sound. Sometimes I can’t do that, but it’s still my job.