I was recently leafing through a Condé Nast Traveller magazine and came upon a page where contributors were asked to share their favourite summer holiday memories. As I sat on the toilet contemplating all the far-flung destinations my travels have taken me to, my head filled with countless pleasant memories created since David and I moved to Dubai fifteen years ago. As a lot of you know, I do not like living in Dubai so much, but I do acknowledge that residing here has given me a pretty remarkable life, full of travel and adventure and the opportunity to make friends all over the world. With a faraway look in my eye, I smiled and reminisced as I tried to settle on just one favourite sun kissed memory.

I thought of our three pilgrimages to Burning Man and in particular that one glorious morning when my friend Marya, David and I all woke up before dawn and cycled a few miles out to the trash fence in skeleton bodysuits to watch the sun rise majestically over the playa. Rubbing our sleepy eyes, we squinted at the champagne coloured clouds from which a dozen or so large black dots appeared to magically materialise.

As we blinked incredulously at the golden light, the dots seemed to get bigger and develop brightly coloured tails. Marya and I glanced at each other, a little alarmed. What was happening? Were we hallucinating? NO! It slowly became apparent that what we were seeing were a number of daring parachutists who had jumped out of a plane at daybreak and were now painting the sky with their rainbow coloured chutes, gracefully trailing beautiful long flags in a wondrous tapestry across the heavens. It was such a beautiful moment and I’ll never forget it, but was it my favourite summer holiday memory?

I didn’t think so, but the floodgates had opened. I remembered wiling away long hot Ibiza days drinking sangria and eating tapas, followed by misspent nights dancing to our favourite DJs. I remembered the simple, but delicious seafood lunch served to us by the captain of a Turkish gulet we’d hired off the Turquoise Coast of Antalya. I remembered hiking the wild and windy coastline of southern Corsica, staying in some random Moroccan billionaire’s summer home that our friends Gwen and Didou were managing for the season. I remembered trekking through vast mountainous canyons to explore the ancient Jordanian city of Petra, and then a few days later bobbing around the Dead Sea, smearing its healing and beautifying mud all over our faces and bodies. And I remembered countless summer days drowsily contemplating the hypnotic cicadas in a tiny ancient hamlet called Adine in Siena, Italy, one of my favourite places on earth. Occasionally we’d summon the energy to drive into town to eat pici served with locally caught wild boar. And afterwards we’d devour nocciola and Amarena gelato while sitting on the cobble stones of the town square, watching toddlers awkwardly chasing pigeons and teenagers awkwardly chasing each other. Later that night David and I chased fireflies in the hamlet’s olive grove.

I remembered trips to Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, Vietnam, Hong Kong, Japan and Taiwan. Mostly just to eat the street food, but also to lounge around on beaches or pools or in izakayas and rooftop bars, kicking off the day-drinking with breakfast beers and seamlessly graduating to lunchtime cocktails and then bottles of wine at dinner. I remembered evenings wandering narrow backstreet warrens looking for the perfect place for a late night meal, and somehow always finding it.

And of course I remembered Greece and her beautiful islands, which I discovered relatively late in life. First Mykonos, and then, in quick succession, Santorini, Milos, Sifnos, Naxos, Zakynthos, Skiathos and Kefalonia. Distinct memories of wandering down overgrown sandy tracks to discover completely secluded beach coves, with the bluest and clearest water I’ve ever seen in my life. Enjoying the simple but delicious food of my childhood, chased down with surprisingly good wine by the kilo. Always followed by the obligatory afternoon siesta. Balmy fragrant nights laden with the promise of a good time floating on the sound of a bouzouki being strummed somewhere. Everywhere. These are all gorgeous memories that I will keep forever. But are they my favourite summer memories? I realised that no, they were not. To access those, I had to go back to Australia. I had to go much further back in time, to my childhood. I had to go back to the farm.

When I was about 12 years old my parents went into cahoots with my aunt Dimi and uncle Alex to buy a plot of land in the Victorian countryside. I remember being dragged around with my sisters to endless real estate inspections of properties on the Mornington Peninsula, about an hour and a half drive from Melbourne, until they eventually found the perfect one. Lot 3, Boneo Road, Cape Schanck was a hilly ten acres of overgrown tea-tree shrubs and native grasses. And that was it. It was wild, it was untamed and it was magnificent. For the next five or six years, we spent most weekends and summer holidays at the farm. And even though it was, in no way, shape or form an actual farm, that was what we called it.

In the beginning, we camped in tents. Later on my Dad laid the foundation for what would come to be known as The Shed. And of course, because it was my Dad, it wasn’t built out of wood or steel or bricks. He built it with materials used by NASA. And I am not even joking about that. The stuff was basically slabs of Styrofoam enclosed in a bright green metallic casing. The shed was four walls and a roof. Our family of five had a tiny bedroom to sleep in, and my aunt and uncle had an even tinier one. My Dad built us all bunk beds. The rest of the shed was an open space kitchen, living, dining area. The floor was a concrete slab. And that was our holiday home. It wasn’t fancy, but it was ours.

Our days and nights were filled with adventures, accompanied by a rotating roster of friends, children of family friends, cousins and even kids off the street. One morning while my sisters and I were playing at the bottom of the driveway three young girls on ponies materialised in front of us and asked us if we wanted to go for a ride. Hell yeah we wanted to go for a ride. Other times the three of us, and whoever happened to be around at the time, would explore the property, trying so hard to get lost, going so deep into the dense tea-tree shrub that we sometimes had to fight through the thickets on our hands and knees, our arms and legs covered in bloody scratches. We were always so disappointed when we hit the fence-line and had to retreat back to the clearing. But that never stopped us from trying again.

I learned how to drive on the farm, in an old unroadworthy Land Rover that needed a crank to start the engine. The same Land Rover that we would all pile into and be jostled around on the 2.5km dirt track down to a secluded, rocky beach that was essentially our own private paradise. I don’t remember seeing more than a handful of people in all the years we spent on that beach, and when I recently tried to find it on a map, I discovered that it still doesn’t even have a name. If you want to find it, it’s somewhere between Gunnamatta and Fingal beaches, but good luck getting to it.

Oh, that beach. It was ours! It was ours! We’d drive down in the morning and stay all day, carrying down platters of homemade food for a sumptuous feast sprawled on the rocks. We’d recline for a while in the shade of a rocky overhang, and afterwards we would fish, always hooking a bounteous catch of butterfish to cook on the BBQ later that day. Sometimes we would search for elusive abalone in the many tidal pools, and sometimes we would be lucky. My Mum would tenderise and pickle it, and cook it up in a stir-fry with rice, the thought of which still makes my mouth water. My sisters and I would confidently leap from rock to rock, like agile little mountain goats. We trudged up massive sand dunes, just so that we could tumble back down them, and then do it all again. And we dove and frolicked in our very special, swimming pool-sized rockpool for hours, exploring every single nook and underwater cranny, trying to catch the little fishies that had been washed in with the previous tide. But they were always quicker than we were, and they were always somehow able to dart away, out of reach of our prune-fingered grasp. This is what favourite summer holiday memories are made of.

Back at the farm we zoomed around on my uncle Alex’s three wheel motorcycle. Oh what a thrill it was to wrap my arms around his waist as he floored it up what felt like an insurmountable summit. The wind whipped my hair around, because it was the 1980s and helmets weren’t a thing. I was always scared that he would rev it just a little bit too much and the two of us would flip backwards. But facing that fear and always reaching the crest and landing those three wheels back on solid ground was an exhilarating experience that I’m fairly sure not many other 14 year old girls were lucky enough to have.

Our hobby farm was right next door to an actual, working farm with a couple of horses and a paddock full of grazing sheep. There were also ducks and chickens and a pigeon coop and a small corn field and a gorgeous black and white Border Collie called Joshua. Every time we drove up the driveway to the farm, Joshua would be there waiting for us. And apart from dinnertime and bedtime he spent every waking minute with our family. He would even chase the Land Rover to the beach, whenever we drove down there, and he’d spend the whole day with us. I don’t know if Farmer Murphy was aware of it or not, but Joshua was our first family dog. We loved him and he loved us.

My sisters and I developed a routine of knocking on the Murphys’ back door every Sunday night, collecting large hessian bags filled with stale loaves of sliced bread and heading down to the pastures to feed the sheep. I remember the first time we did this. We entered the enclosure and clicked the gate behind us. It felt like every single sheep in that three acre pasture stopped what they were doing and looked up at us. And then, the sheep started running. A hundred sheep stampeding towards three nervous young girls holding sheep food. I’m pretty sure we all started screaming, and I’m pretty sure I thought the three of us were going to die. And as they approached us and the fear escalated, somehow, we started running back towards them and the killer sheep dispersed. And we laughed and laughed, mostly as a release to the fear, but also because it was just funny. And we started throwing slices of bread all over the place and the sheep lunged at it like ravenous wild animals. And when we ran out of bread, the sheep just disinterestedly sauntered away. As if nothing incredible or mind-blowing had just happened.

The Murphy’s were really nice to us, letting us feed their sheep and steal their dog. They sometimes even let us chase around the cute little springtime ducklings and chicks that had just hatched. But the truth is that they probably didn’t love us being there. We were a rowdy bunch of Greek immigrants who would often be up until the wee hours of the morning revelling and carousing and generally being festive motherfuckers! I remember one particularly merry night, my Dad was playing guitar and Alex, taken with the spirit, grabbed a drawer from his bedroom dresser, theatrically flipping the contents on the floor and, with his leg up on a chair, started using it as a drum, rhythmically banging the shit out of it. My Mum, inspired, grabbed a coffee jar full of rice from the kitchen to use as another instrument in this unhinged jam session, and everyone danced and sang along. We kids watched in wonder as our normally mannerly relatives just rocked the fuck out. The carefree exuberance and unbridled high spirits of moments like these stay with me, and fill me with joy decades later. These are what favourite summer holiday memories are made of.

Sometimes the singalongs came at the end of the night. Sometimes they were the opening act. Depending on the tides, sometimes my sisters and I would be woken up at one or two in the morning and then we’d all drive down to the Fingal Beach hiking trails. A dozen of us carting buckets, torches and gardening gloves, we traipsed down the steep, sandy steps to the rocky beach below to catch crabs. As the tides started going out, the crabs would emerge from the rockpools in search of food and we would be there to grab them. We were young kids running around in the middle of the night in gum boots on jagged rocks catching crabs as the tide went out into an inky black, and sometimes wild, roaring sea. Hell yeah!

The cliff path might have felt like a thousand steps going down, but it felt like a million steps climbing back up with buckets full of salivating crabs. We’d drive back to the shed, put a huge pot of water on the stove to boil and enjoy a glorious supper of the most ridiculously tasty, freshly caught seafood bonanza you could ever imagine. The memory of cracking open a thick leg to pull out delicious, tender, meaty morsels of crab at 3 o’clock in the morning, bleary eyed and surrounded by my loved ones has to be one of my favourite summer holiday memories in a life filled with them.

I spent those years on the farm being a free and feral child, living a wild and precious life. Whenever David and I go back home to visit Australia, my sisters and I always make sure to get together at Fingal Picnic Area where we used to barbeque the butterfish that we caught on our private beach all those years ago. We gather now to reminisce about those good old days, and to pay our respects and to honour the memory of the wonderful childhood our parents gave us.

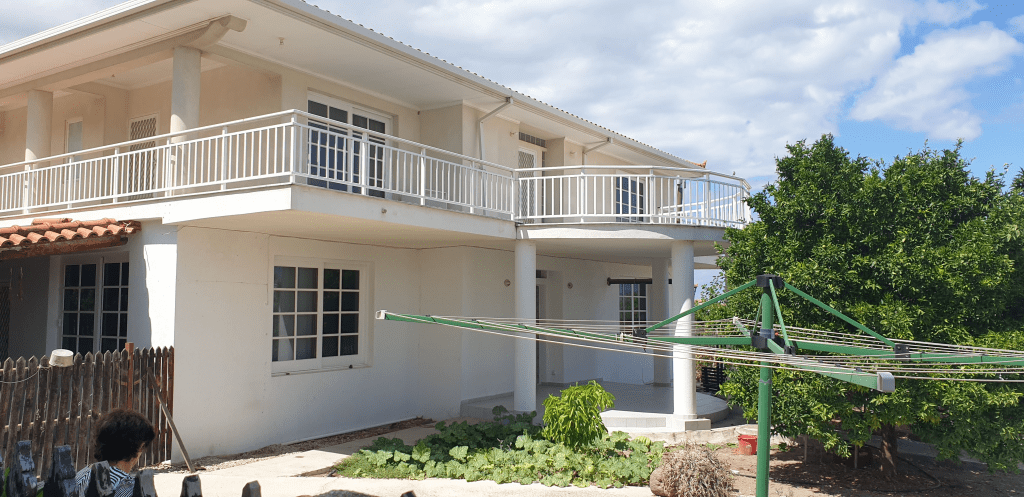

We were there just a few days ago and on our drive to the picnic area, I asked to stop off at Lot 3, Boneo Road. A gorgeous new house has since been built on the highest point of the property, but the old shed is still there. A little nervously, we walked (trespassed?) up the driveway to the shed which is now being used as a garden shed. The exterior has been painted black, but inside it’s still bright green. The old grape trellis my father built is in total disrepair, and the garden my Mum cultivated is a riot of wild grape vines, passionfruit plants and lemon trees. But, most notably, nature has fiercely taken back what was once hers. The natural world that we constantly had to fight off to build the shed, and to live in the shed during our summer holidays, has won the battle. Mother Nature, biding her time, grew back with a vengeance, surrounding the shed, enveloping it and ultimately reclaiming her space. My Mum and Dad are gone. Alex is gone. One day Mary, Pieta, Dimi and I will be gone, and every single memory of those summer days down at the farm will be gone. But as we stood there the other day, looking at this familiar, cubic building that somehow seems to have become part of the landscape of what used to be the farm, I found that there was something really beautiful about that. The farm now belongs to someone else. The shed, still standing nearly 40 years after my Dad built it, belongs to someone else. And yet somehow it still all belongs to us. It will always belong to us.